In my last post I presented a malware analysis solely based on the dynamic technique using OllyDbg. The goal was to recover the algorithm that was used for domain name generation of the C&C server. Knowing, that there is no one best tool for everything but rather the best tool for a particular problem, I’ve decided to try and solve the same challenge with the help from static analysis tools, like IDA (free edition), while minimizing Olly involvement. Correct me, if I’m wrong, but it’s rather difficult to unpack the exe with IDA then with Olly, so I used the later tool to unpack the code and load all the needed API functions. Finally, I dumped the “real” code from memory for further analysis in IDA.

Some pitfalls

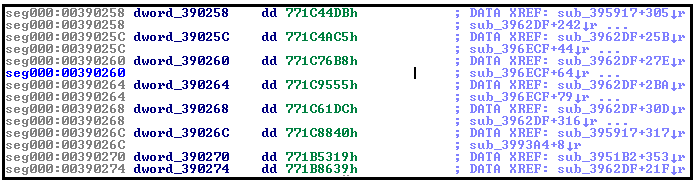

After IDA’s initial dump analysis, I realized that there were some things that were missing. Those addresses of the Win32 API functions, that were dynamically resolved by the unpacker had missing labels (Fig 1). Without those labels, it would be quiet difficult to do the analysis and try to find anything. No labels in IDA

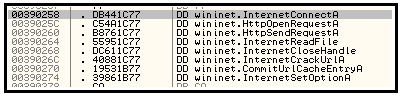

And just for comparison, in OllyDbg the same addresses are looking more friendly:

To give those addresses some meaning in IDA, Volatility framework was used to generate the name for each of those addresses:

- While the debugger is still attached to the sample, dump all the RAM of the machine (moonsols toolkit).

- Find the PID of the debuggee using the pslist Volatility plugin.

- Using the

impscanplugin, generate the IDC commands for IDA, which will give the addresses the appropriate names.

And one more thing, when IDA analyzes the dump it needs someone to tell it, from where to start. From that point, it recursively can get to any function that is called by parent function, by child function and so on. Still, there are parts of code that are not called by any function, meaning IDA can not get there on its own to analyze them. In this particular case, those parts were functions that were executed in different threads. Identifying call sites to the “thread-creating” functions, one can point IDA to the missed code for further analysis.

Solving the puzzle

So again, the goal is to find the algorithm that is used to generate the domain names for the C&C servers. As in the previous post, I started by looking for the functions that are involved in communications and may accept domain names as parameters, mainly:

HINTERNET InternetConnect(

_In_ HINTERNET hInternet,

_In_ LPCTSTR lpszServerName,

_In_ INTERNET_PORT nServerPort,

_In_ LPCTSTR lpszUsername,

_In_ LPCTSTR lpszPassword,

_In_ DWORD dwService,

_In_ DWORD dwFlags,

_In_ DWORD_PTR dwContext)

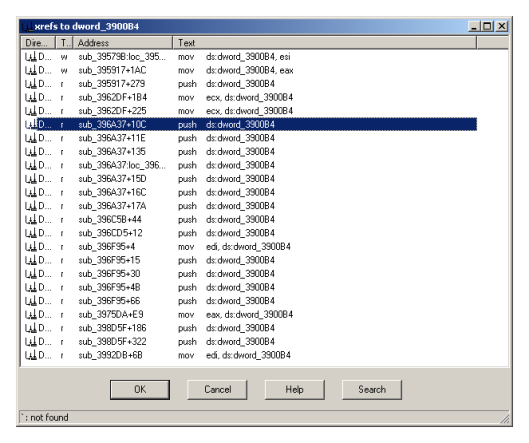

The starting point is the second parameter of the InternetConnect function which is passed from some global buffer 0xdword_3900B4. Using cross-referencing on the 0xdword_3900B4 showed 23 references to it (Fig 3).

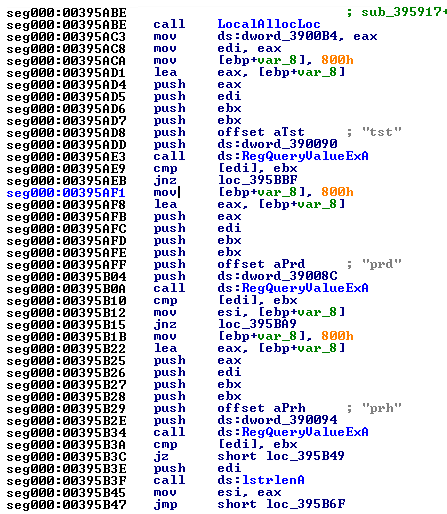

A quick check of the listed locations showed an interesting function (Fig 4). Here one can spot a lot of queries to the registry for specific keys while trying to verify if those keys are initialized.

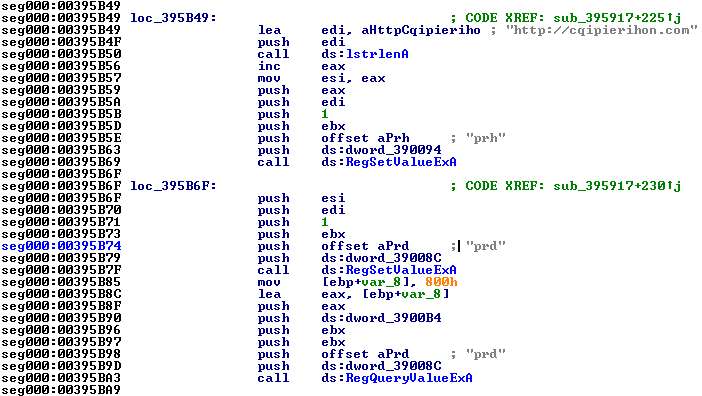

And if they are empty, the initialization occurs (Fig 5) with predefined domain name. So from here, we got another clue in the puzzle – the prd and prh registry keys are used to store domain names – just remember them and we’ll get back to them shortly.

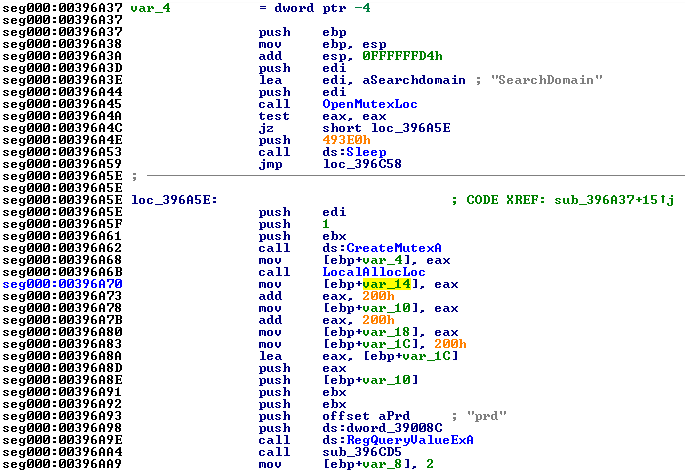

This function has served it’s purpose and we can return to our list. Speaking of which, the cross-reference list itself could sometimes be very helpful as just by examining it, one could see additional clues. In this particular case, it did help by reviling the function (sub_396A37) which used heavily the 0xdword_3900B4 buffer (Fig 3) that could be worth investing time into. And before digging any further some more checks showed that this function indeed responsible (at least partially) for the domain name generation (Fig 6) as the mutex name may suggest.

In addition, if you remember the prd registry key – it was holding some domain name and right here we see buffer allocation and registry query to get this key contents into the new buffer. Just after that, there is a non-ordinary function (sub_396CD5) which operates on the same local variables as the caller does (Fig 7).

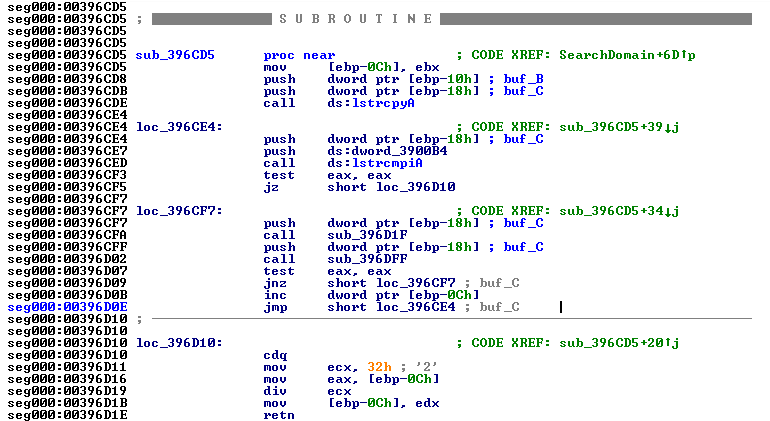

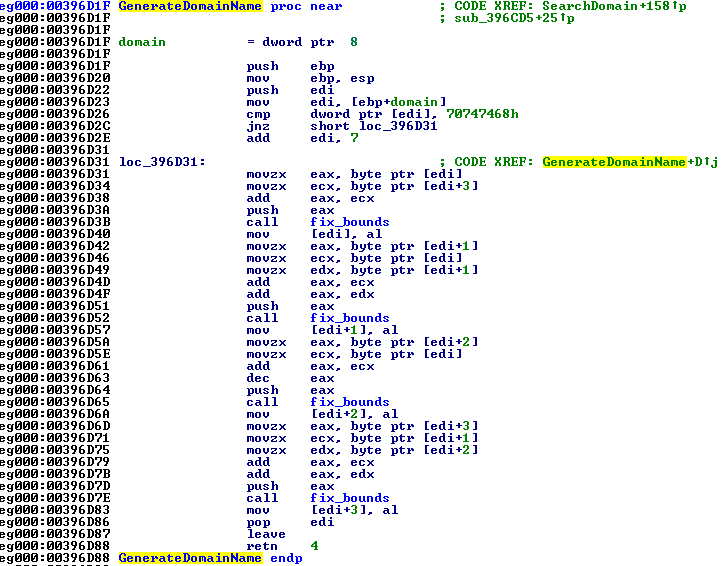

It’s purpose is to check the validity of the registry-stored domain name against a block-domain list file. When the pool of the names is exhausted, the file is deleted and everything re-starts while the actual domain name generation is based on the following code (Fig 8).

or in a more readable form:

fix_bounds(char &letter)

{

char bound = 0x1A;

letter = letter - 0x61;

while(letter > bound)

{

letter = letter - bound;

}

letter = letter + 0x61;

}

search_domain(char *domain)

{

char *tmp_domain = domain;

if (first 4 bytes is "http")

tmp_domain = tmp_dom

in + 7;

letterA = tmp_domain[0];

letterB = tmp_domain[3];

latterA = letterA + letterB;

fix_bounds(letterA);

tmp_domain[0] = letterA;

letterA = tmp_domain[1];

letterB = tmp_domain[0];

letterC = tmp_domain[1];

letterA = letterA + letterB + letterC;

fix_bounds(letterA);

tmp_domain[1] = letterA;

letterA = tmp_domain[2];

letterB = tmp_domain[0];

letterA = letterA + letterB - 1;

fix_bounds(letterA);

tmp_domain[2] = letterA;

letterA = tmp_domain[3];

letterB = tmp_domain[1];

letterC = tmp_domain[2];

letterA = letterA + letterB + letterC;

fix_bounds(letterA);

tmpain[3] = letterA;

}

I hope, you was able to follow me through the post and learned something new as I did. Any comments are more then welcome and could be left here or to my mail.