There were many thoughts about what should I write about in my first time ever post in my own reversing blog. Fortunately for me, my will to publish my findings and the reversing challenge, that my good friend has kindly pointed me to, resulted in the birth of this first post. So, I’d like to write about the steps I took to accomplish the challenge and what eventually I’ve learned from it at the end. I hope someone will find something new and enriching for himself here as I did. I’ll be very glad to hear any comments on this post. So, here we go.

The Challenge

The challenge page has pointed me to some binary and the goal was to find out the algorithm that the binary used to prepare something before it communicates with its CnC. The algorithm must be converted from the assembly to the high level language representation.

The Plan

Despite the fact, that I’m really new to the reversing world, I’ve already learned that I must decide as precise as possible what I’m looking for, before I’m even diving into the binary. So, considering the above and the challenge question, my starting point was to look for functions involved in communications and examine them for unique parameters:

- communication protocol

- domain names

Research results

unPacking

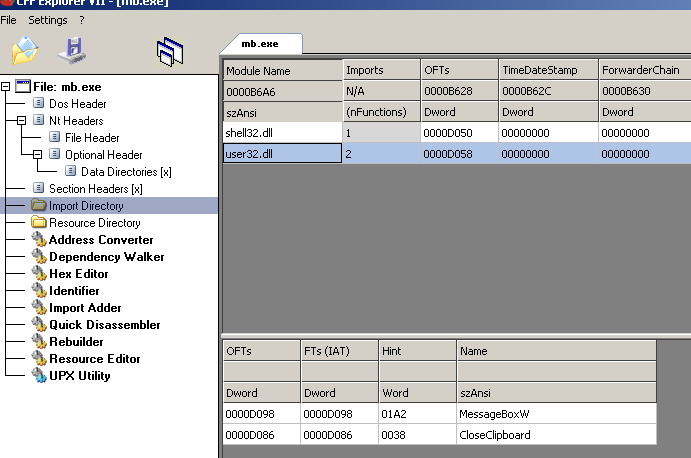

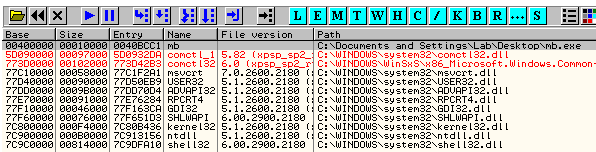

So, we are looking for an API call that could establish communication with the outer world. Let’s take a look at import table and try to find such API:

This table looks pretty empty to me as it has a very small number of functions and not the ones I’m looking for. In addition a small check in IDA for file layout showed little code and lots of data:

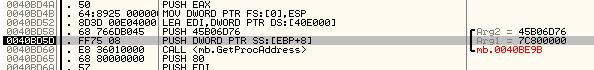

So, I guess the author has packed the file and the probable solution to this situation is to get closer to our buddy with my other friend Olly. After the opening of the file in Olly, I’ve landed at the Entry Point and little examination has showed that it was responsible for analyzing the stack and calculating the base address of kernel32.dll module. There were hard coded values of function offsets from the base address of the kernel32:

The important ones were :

- GetCurrentProcessID

- OpenProcess

- VirtualAlloc

- VirtualProtectEx

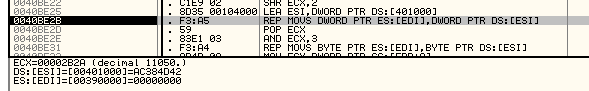

which were used to allocate space and move there 0x2B2A bytes of data:

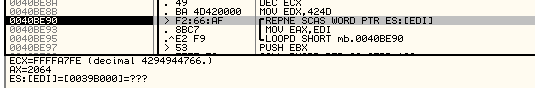

and it can be seen that the data is taken from the start of the file – remember IDA analysis we have seen earlier. On the next step, the moved code was decrypted and the control transferred to it using SEH for “Access Violation Exception”:

Adventure begins

So, once at the Entry Point (after the decryption) the first thing to check if we are able to transmit to the outer world. Loaded modules list shows nothing of particular interest which means, the malware needs to load libraries before doing anything “useful”:

And after the load is finished, different picture emerges:

Looking at the Fig.7, one can notice two libraries that could be used for communication – winInet.dll and ws2_32.dll. As winInet.dll requires the second one, let’s concentrate on the winInet.dll at first. Analyzing inter-modular calls, I was hoping to find a very specific functions that initiate the connection and send the data to the remote host:

InternetConnect– the functions contains the actual server that malware wants to connect to, probably having the dynamic name generation.HttpSendRequest– the functions responsible for sending the request which could contain dynamic parts, like ID of the session/machine on which it is installed.

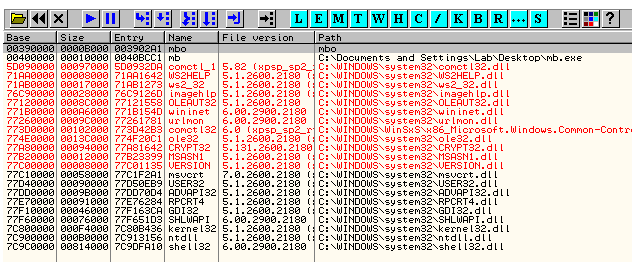

Fortunately for me, there were not so many references to the above functions, so I’ve decided to start from the second function – HttpSendRequest. Following the first reference call, I’ve landed at the calling function which looked very promising as it was responsible, among other things, for request string generation.

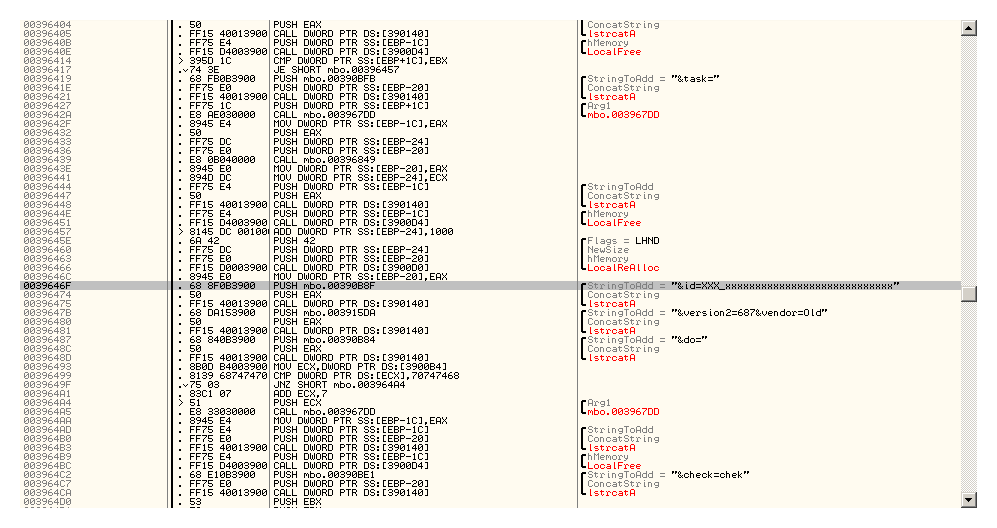

Going over the request generation (Fig. 8), I’ve found the id parameter which was concatenated with XXX_xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx. This looks like some reserved space to me. To verify my “intuition”, I’ve followed the execution of the malware and monitored the above string which was stored at [0x00390B93]. Eventually, the XXX_… was replaced with USA_VkJlY2ZkNGRiZi1lY2RiNTljMl8 and BINGO, I was right. So now, the question is, how this id was generated. I looked for the references to the pre-allocated buffer in the code. The reference list showed only 4 potential places to start the quest from. Quickly analyzing them, I concentrated only on one of them:

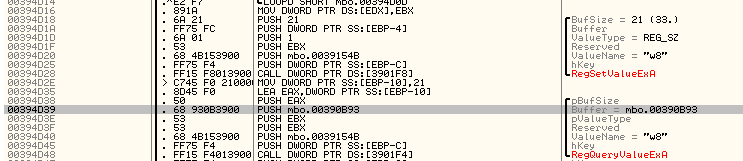

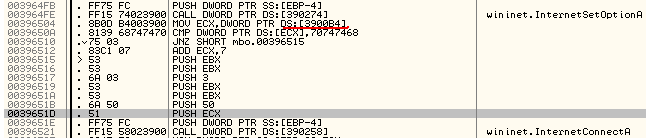

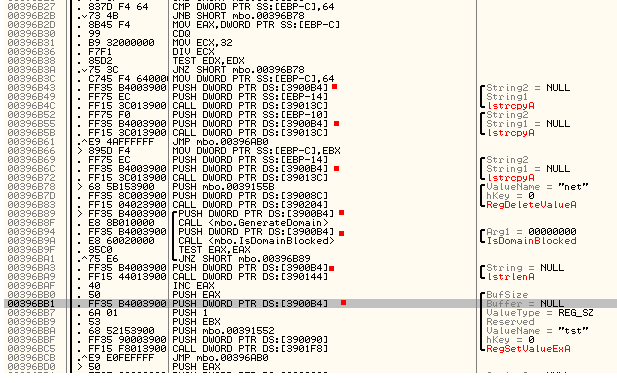

The special thing about this place was the fact that this buffer was used to store the data from the registry query with the key name w8. Obviously, if there was a query for that value, there was some place that it was responsible to store it in the first place. Fortunately, this place was right above my current position. RegSetValueExA API call and the buffer with the needed data was at [EBP-4] which is the one, I need to follow to get to the initial calculation of the id. This being said, I jumped to the beginning of the function to start the tracking.

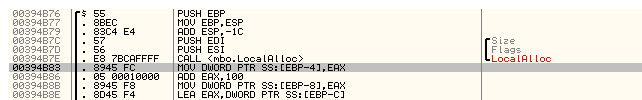

It was easy to see, that [EBP-4] got the address of the allocated buffer and in addition we get a new player in the game – [EBP-8] which points 0x100h bytes further in the newly allocated memory. Deeper into the function, it could be seen that those two “buffers” are actually parameters that are supplied to 2 functions, where [EBP-4]:

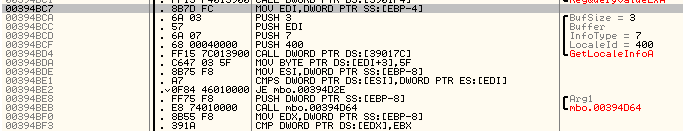

gets the locale info as the result of calling GetLocaleInfoA and this is actually shows why we had USA in the final id as my lab computer had USA English locale, and [EBP-8] got supplied to some local defined function. The examination reviles that the uniqueness of the id is based on the DeviceIoControl with the following supplied parameters:

Where IoControlCode and InBuffer (StorageDeviceProperty = 0) are of particular interest, because it results in the filling the following struct holding the HDD information:

typedef struct _STORAGE_DEVICE_DESCRIPTOR {

DWORD Version;

DWORD Size;

BYTE DeviceType;

BYTE DeviceTypeModifier;

BOOLEAN RemovableMedia;

BOOLEAN CommandQueueing;

DWORD VendorIdOffset;

DWORD ProductIdOffset;

DWORD ProductRevisionOffset;

DWORD SerialNumberOffset;

STORAGE_BUS_TYPE BusType;

DWORD RawPropertiesLength;

BYTE RawDeviceProperties[1];

} STORAGE_DEVICE_DESCRIPTOR, *PSTORAGE_DEVICE_DESCRIPTOR;

where the final key piece of data is a serial number of the drive. The serial number of the drive is actually transferred to the third function as a dictionary the final part generation of the id and this based on the following algorithm:

func generate_key(dic, result)

{

dic_len = strlen(dic)

counter = 0

while (counter < dic_len)

{

flag = 1;

while (flag >= 0)

{

letter = 0

round = 0

while (round < 2)

{

letter = letter * 2^4;

index = counter + round + flag * 2;

val = dic[index];

if (val < 0x20)

return;

if (val <= 0x3A)

val = val - 0x30;

else

val = val - 0x57;

letter = letter + val;

round++;

}

if (letter != 0)

{

result[strlen(result)] = (char)letter;

}

flag--;

}

counter = counter + 4;

}

}

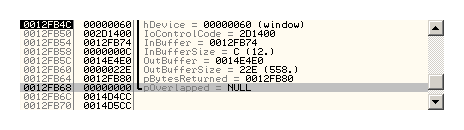

In addition to the above, it appeared that domain names were also dynamically generated. Looking into inter-modular calls in Olly, I’ve noticed 3 calls to InternetConnectA which among its parameters had a domain name. Those 3 functions were the starting points.

The idea is to follow the second parameter and look for the peace of code that changes it. So, as the Fig. 13 shows, the address of interest is 0x3900B4h.

Olly presented not very long list of references to the buffer and its examination did not take much time and effort. In many places it was used to store the data, that was retrieved from the registry query. In addition one of the examined function reviled that buffer data was saved by the following registry keys: “*pre*”, “*net*”, “*tst*” and “*prh*” and examining Fig. 14 it can be seen that probably altered 0x3900B4h buffer was saved again by the “*tst*” key.

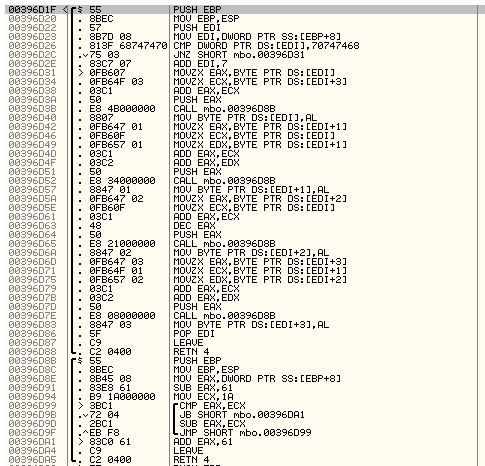

Based on the above findings the analysis was concentrated inside the function that was shown on Fig.14. Going over the Fig. 14 code, I spotted a loop that was constantly waiting to get a positive result while the only parameter to the function was the buffer of interest. Diving at the address 0x396B8F the following function is observed as on Fig. 15 which clearly changes the initial buffer

and translating the code into something more readable:

fix_bounds(char &letter) {

char bound = 0x1A;

letter = letter - 0x61;

while(letter > bound) {

letter = letter - bound;

}

letter = letter + 0x61;

}

search_domain(char *domain) {

char *tmp_domain = domain;

if (first 4 bytes is "http")

tmp_domain = tmp_domain + 7;

letterA = tmp_domain[0];

letterB = tmp_domain[3];

letterA = letterA + letterB;

fix_bounds(letterA);

tmp_domain[0] = letterA;

letterA = tmp_domain[1];

letterB = tmp_domain[0];

letterC = tmp_domain[1];

letterA = letterA + letterB + letterC;

fix_bounds(letterA);

tmp_domain[1] = letterA;

letterA = tmp_domain[2];

letterB = tmp_domain[0];

letterA = letterA + letterB - 1;

fix_bounds(letterA);

tmp_domain[2] = letterA;

letterA = tmp_domain[3];

letterB = tmp_domain[1];

letterC = tmp_domain[2];

letterA = letterA + letterB + letterC;

fix_bounds(letterA);

tmp_domain[3] = letterA;

}